EVIDENT serious game

Imagine that you have just come home from a long and busy day of work. You are tired and looking forward to a relaxing evening. You open your door, walk into your kitchen, and find water all over the floor. You realise your washing machine has broken, and just when it is out of warranty. What would you do in this scenario? How would you determine whether you should get a repair-person to fix your washing machine, or whether you should get a new one?

This is a decision many individuals struggle with, as it requires you to balance the anticipated cost of repair, the lifespan of the appliance, its energy rating and history of repair, against the cost, energy rating and lifespan of a new appliance. When faced with this choice, consumers often fail to choose the option that has the best financial and environmental consequences for them. The EVIDENT serious game aims to address this by 1) expanding our understanding of factors that impact the repair/replace decision; and 2) helping consumers understand how they may make more effective choices.

Factors impacting repair/replace decision making

Repair/replace decision

Households don’t tend to consider energy efficiency, even when it is in their best interests. Research suggests that only around 47% of people are aware of their monthly energy use [1]. While energy is a large part of household monthly expenditure, individuals are unaware of how their choices impact these costs. This is often due to inattention, lack of energy literacy [2] or challenges interpreting bills [3]. These misperceptions lead to energy over-use, and when consumers are unaware of their energy costs it is difficult for them to determine how savings may be made through more efficient appliances (Filippini et al., 2020). While many technologies been developed to support consumers to use less energy, poor adoption and miss-use means consumers often miss out on the potential cost savings [4]. This is known as the energy efficiency gap [5].

This may also make repair/replace decisions more challenging because without an understanding of energy use and cost it can be more difficult to decide between similar appliances [6]. The decision making process, when faced with a broken appliance, also may differ depending on whether you own your home, are a tenant, or offer a home for others to rent. This distinction is noteworthy, as around 30% of people in the EU are tenants [7]. Decisions for those in rental accommodation may differ from homeowners, and may be more complicated due to the multiple groups involved. While property owners who rent to others are often responsible for purchasing or replacing appliances, they do not see any of the resulting energy savings. Opposingly, tenants pay the energy costs, but often do not have input into the choice of appliances in the accommodation. This is known as a split incentive, and acts as a barrier to energy efficiency investments. In order to address these challenges for the large volume of rental properties, we need to explore the factors which impact energy decisions for this group.

Why use a serious game ?

Residential electricity consumption has enormous energy-saving potential, with savings of 31% possible through the uptake of more energy efficient appliances, and by supporting more efficient energy choices [8]. In order to reduce energy consumption, wide-scale behaviour change is needed. While many behaviour change interventions have been developed to address residential consumption [9], [10], engagement with these interventions remains a key challenge. Common factors which negatively impact engagement with energy behaviour change interventions include lack of interest and a reluctance to change [11]. Energy behaviour is particularly difficult to change as there is often a lot of time between the decision to use energy (i.e. turning on a light switch), and obtaining feedback on that energy use (i.e. through an energy bill). This high temporal latency (or gap in time) makes it difficult to understand the impact of our actions on our energy costs [12]. A further complication is the balance between the effort to change behaviour, and the impacts. While energy behaviour change requires significant effort, impacts on finances and energy use are often small [13]. To address these challenges in engagement in behavioural interventions, new approaches are needed relating to how we present these behaviour change interventions. Serious games are one such approach.

What is a serious game ?

Serious games are defined as the use of gamification outside traditional gaming contexts, with the goal of supporting behaviour change or learning, while providing entertainment or fun for those playing the game. Put simply, serious games provide an interactive environment which aims to guide behaviour change, while maintaining player fun and engagement. Serious games provide players with the opportunity to explore the impact of their behaviours in a simulated environment, where the real-life consequences are removed [14]. And a serious game about energy efficiency would allow players to learn how they may make better energy decisions in real-life contexts. Serious games aim to support engagement in behaviour change interventions through the use of gamification strategies such as feedback, self-monitoring, competition, sharing with peers, rewards, leader boards and rankings [14]. To ensure the learnings of serious games carry through to real world settings, objective measures of behaviour are often included, such as actual energy consumption. Serious games have been shown to be effective in a variety of settings including consumption awareness, education and pro-environmental behaviour [15].

The EVIDENT serious game

The EVIDENT serious game was developed to order to address 1) the engagement challenge in energy behaviour change intervention; and 2) the need to explore the factors which impact repair/replacement decision making for consumers.

There are two primary aims of the EVIDENT serious game. The first aim is to explore the factors which impact household decisions to repair or replace appliances. Specifically, the impact of financial literacy (i.e. the ability to understand and manage your money), demographic factors (i.e. age, socio-economic status, house type, etc), and behavioural intention (i.e. how willing you are to change your behaviour) on decisions to repair or replace appliances for different residential types (i.e. owner-occupier, tenant, or property owner who rents to others), will be examined. The second aim is to help consumers to understand how they can make more effective repair/replace decisions, when considering both the financial and environmental impacts.

What is the EVIDENT serious game ?

The EVIDENT serious game is a life simulation type game in which players are tasked with maintaining a home over the passing of time. Players are assigned a character that matches their residential status (i.e. property owner who rents to others, tenant or homeowner), and can move this character around their virtual home. Players must complete a series of actions to keep their characters comfortable, while making sure their energy use or spending doesn’t get too high. Players will be guided by gauges which will show their comfort, environmental impact (based upon Kw/h of energy use within the game) and finances, allowing them to see the impact of their actions and what changes they may need to make.

Image from EVIDENT serious game

During the game, players will be presented with an alert that an appliance in the home is malfunctioning, and will have to decide whether to repair or replace this appliance. To make this decision, players have to negotiate with a repair-person to try to make the most financially and environmentally effective decision. After this first decision is made, players will be given feedback and information on how to approach repair/replace decisions in future.

Repair person negotiation in EVIDENT serious game

At the end of the game, participants will be given a final score based on their environmental impact, comfort and finances and can see where they fall on a leader board. This will allow players to compare scores with peers, and to see where they score relative to others.

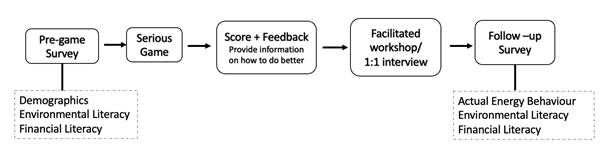

In order to address the aims of the serious game, pre- and post-game surveys will be conducted. These surveys will establish participant financial and environmental literacy to allow us to determine the impact of these factors on repair/replace decisions. A follow-up survey will also be conducted six to twelve months after the serious game to allow researchers to explore the impact of the serious game on real world behaviour. Participants will be asked if opportunities to make repair/replace decisions arose, and what they decided. Qualitative analyses will also be conducted following on from the serious game, using both individual interviews and focus groups, to further explore the impact of the game and identify additional barriers or facilitators to energy decision making.

Procedure for the Serious Game

Next steps

A key step in the development of serious games is usability analysis. Usability analysis involves getting people to play the serious game and test the extent to which it is usable, makes sense, and is fun to play. Through gathering this input we can ensure that the serious game will be usable by those for whom it is intended. When completing usability analyses, it is important to ensure that those who test the game are representative of all the different types of game players, so that we can be sure that the game is relevant for all population groups.

Across the next month we will start to complete some usability analyses for the EVIDENT serious game. This will involve asking individuals or groups to play the serious game and share their feedback with us on how it may be improved. Feedback will be gathered through individual short surveys, and through focus groups. Recommendations will be gathered, and the serious game will be updated in line with these recommendations.

How can I get involved?

If you are interested in playing the serious game, there are lots of ways you can get involved.

- You can take part in the usability analysis, where you will have the opportunity to play the game and share your thoughts in a short survey.

- You can join a usability focus group. Here you will have the opportunity to play the game and then join a discussion to share your thoughts.

- Make sure to follow the EVIDENT project social media to be first to know when the game is fully available.

If you are interested in participating in the usability analysis, please email delemere@tcd.ie

Referecnes

[1] Brounen, N. Kok, and J. M. Quigley, “Energy literacy, awareness, and conservation behavior of residential households,” Energy Economics, vol. 38, pp. 42–50, Jul. 2013, doi: 10.1016/j.eneco.2013.02.008.

[2] J. Blasch, N. Boogen, M. Filippini, and N. Kumar, “Explaining electricity demand and the role of energy and investment literacy on end-use efficiency of Swiss households,” Energy Economics, vol. 68, pp. 89–102, 2017, doi: 10.1016/j.eneco.2017.12.004.

[3] B. Gilbert and J. Zivin, “Dynamic Salience with Intermittent Billing: Evidence fromSmart Electricity Meters,” Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, vol. 107, Mar. 2014, doi: 10.1016/j.jebo.2014.03.011.

[4] L. Yang, X. Chen, J. Zhang, and H. V. Poor, “Cost-effective and privacy-preserving energy management for smart meters,” IEEE Transactions on Smart Grid, vol. 6, no. 1, pp. 486–495, 2014.

[5] T. D. Gerarden, R. G. Newell, and R. N. Stavins, “Assessing the Energy-Efficiency Gap,” Journal of Economic Literature, vol. 55, no. 4, pp. 1486–1525, Dec. 2017, doi: 10.1257/jel.20161360.

[6] J. Blasch, M. Filippini, and N. Kumar, “Boundedly rational consumers, energy and investment literacy, and the display of information on household appliances,” Resource and Energy Economics, vol. 56, pp. 39–58, May 2019, doi: 10.1016/j.reseneeco.2017.06.001.

[7] Eurostat, “Housing in Europe.” 2020. Accessed: Jul. 05, 2021. [Online]. Available: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/cache/digpub/housing/index.html?lang=en

[8] S.-V. Oprea, A. Bâra, and A. Reveiu, “Informatics Solution for Energy Efficiency Improvement and Consumption Management of Householders,” Energies, vol. 11, no. 1, pp. 1–31, 2018.

[9] J. Doe and D. Francis, “What are we doing here? Analyzing fifteen years of energy scholarship and proposing a social science research agenda,” International Journal of Social Studies, vol. 1, no. 1, 2021.

[10] C. Seligman, J. M. Darley, and L. J. Becker, “Behavioral approaches to residential energy conservation,” Energy and Buildings, vol. 1, no. 3, pp. 325–337, Apr. 1978, doi: 10.1016/0378-7788(78)90012-9.

[11] B. K. Sovacool, P. Kivimaa, S. Hielscher, and K. Jenkins, “Vulnerability and resistance in the United Kingdom’s smart meter transition,” Energy Policy, vol. 109, pp. 767–781, Oct. 2017, doi: 10.1016/j.enpol.2017.07.037.

[12] J. Burgess and M. Nye, “Re-materialising energy use through transparent monitoring systems,” Energy Policy, vol. 36, no. 12, pp. 4454–4459, Dec. 2008, doi: 10.1016/j.enpol.2008.09.039.

[13] DEWHA, “Energy use in the Australian residential sector 1986-2020, Part 1.” 2008. Accessed: Jan. 28, 2022. [Online]. Available: http://www.environment.gov.au/settlements/energyefficiency/buildings/index.html

[14] D. Johnson, E. Horton, R. Mulcahy, and M. Foth, “Gamification and serious games within the domain of domestic energy consumption: A systematic review,” Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, vol. 73, pp. 249–264, Jun. 2017, doi: 10.1016/j.rser.2017.01.134.

[15] L. Morganti, F. Pallavicini, E. Cadel, A. Candelieri, F. Archetti, and F. Mantovani, “Gaming for Earth: Serious games and gamification to engage consumers in pro-environmental behaviours for energy efficiency,” Energy Research & Social Science, vol. 29, pp. 95–102, Jul. 2017, doi: 10.1016/j.erss.2017.05.001.

This project has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant agreement No

This project has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant agreement No